History of Ju Jitsu

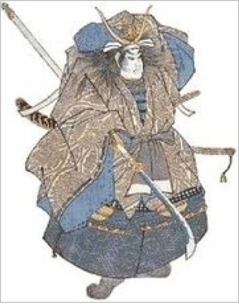

Ju-jitsu (from the Japenese ju-jitsu meaning "gentle/ yielding/ compliant art") is a Japanese martial art whose central ethos is to yield to the force provided by an opponent's attack in order to apply counter techniques from the resultant ensuing situation. There are many ryu (styles) of the art which leads to a diversity of approaches. Ju-jitsu ryu may utilize all techniques to some degree (i.e. Throwing, trapping, locking, holding down, grappling, gouging, biting, disengagements, Strike, and kicking). Generally ju-jitsu ryu make limited use of strikes since they were predominantly developed in feudal Japan under the auspices of the samurai warrior class. The techniques evolved to become effective against armed opponents wearing bamboo body armour to protect vital parts of the face, throat, and body. In addition to ju-jitsu, many schools taught the use of weapons.

Origins

Fighting forms have existed in Japan for centuries. The first references to such unarmed combat arts or systems can be found in the earliest purported historical records of Japan, the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) and the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan), which relate the mythological creation of the country and the establishment of the Imperial family. Other glimpses can be found in the older records and pictures depicting sumai (or sumo) no sechie, a rite of the Imperial Court in Nara and Kyoto performed for purposes of divination and to help ensure a bountiful harvest.

There is a famous story of a warrior Nomi no Sekuni of Izumo, who defeated and killed Tajima no Kehaya in Shimane prefecture while in the presence of Emperor Suinin. Descriptions of the techniques used during this encounter included striking, throwing, restraining and weaponry. These systems of unarmed combat began to be known as Nihon koryu jūjutsu (Japanese old-style jutsu), among other related terms, during the Muromachi period (1333-1573), according to densho (transmission scrolls) of the various ryuha (martial traditions) and historical records.

Most of these were battlefield-based systems to be practiced as companion arts to the more common and vital weapon systems. These fighting arts actually used many different names. Kogusoku, yawara, kumiuchi, and hakuda are just a few, but all of these systems fall under the general description of Sengoku jūjitsu. In reality, these grappling systems were not really unarmed systems of combat but are more accurately described as means whereby an unarmed or lightly armed warrior could defeat a heavily armed and armoured enemy on the battlefield. Ideally, the samurai would be armed and would not need to rely on such techniques.

Methods of combat (as just mentioned above) included striking (kicking and punching), throwing (body throws, joint-lock throws, unbalance throws), restraining (pinning, strangulating, grappling, wrestling) and weaponry. Defensive tactics included blocking, evading, off-balancing, blending and escaping. Minor weapons such as the tanto (dagger), ryufundo kusari (weighted chain), jutte (helmet smasher), and kakushi buki (secret or disguised weapons) were almost always included in Sengoku jujitsu.

Development

In later times, other koryu developed into systems more familiar to the practitioners of Nihon ju-jitsu commonly seen today. These are correctly classified as Edo ju-jitsu (founded during the edo period): systems generally designed to deal with opponents neither wearing armor nor in a battlefield environment. For this reason, most systems of Edo ju-jitsu include extensive use of atemi waza (vital-striking technique). These tactics would be of little use against an armored opponent on a battlefield. They would, however, be quite valuable to anyone confronting an enemy or opponent during peacetime dressed in normal street attire. Occasionally, inconspicuous weapons such as tanto (daggers) or tessen (iron fans) were included in the curriculum of Edo ju-jitsu.

Another seldom seen historical aside is a series of techniques originally included in both Sengoku and Edo ju-jitsu systems. Referred to as hojo waza ( hojojitsu, nawa jitsu, hayanawa and others), it involves the use of a hojo cord, (sometimes the sageo or tasuke) to restrain or strangle an attacker. These techniques have for the most part faded from use in modern times, but Tokyo police units still train in their use and continue to carry a hojo cord in addition to handcuffs. The very old Takenouchi-ryu is one of the better-recognized systems that continue extensive training in hojo waza.

Many other legitimate Nihon ju-jitsu ryu exist but are not considered koryu (ancient traditions). These are called either Gendai ju-jitsu or modern ju-jitsu. Modern jujitsu traditions were founded after or towards the end of the Tokugawa period (1603-1868). During this period more than 2000 schools (ryu) of ju-jitsu existed. Various traditional ryu and ryuha that are commonly thought of as koryu ju-jitsu are actually gendai ju-jitsu. Although modern in formation, gendai ju-jitsu systems have direct historical links to ancient traditions and are correctly referred to as traditional martial systems or ryu. Their curriculum reflects an obvious bias towards Edo ju-jitsu systems as opposed to the Sengoku ju-jutsu systems. The improbability of confronting an armor-clad attacker is the reason for this bias.

Over time, Gendai ju-jitsu has been embraced by law enforcement officials worldwide and continues to be the foundation for many specialized systems used by police. Perhaps the most famous of these specialized police systems is the Keisatsujutsu (police art) Taiho jutsu (arresting art) system formulated and employed by the Tokyo Police Department.

If a Japanese based martial system is formulated in modern times (post Tokugawa) but is only partially influenced by traditional Nihon ju-jitsu, it may be correctly referred to as goshin (self defense) ju-jitsu. Goshin ju-jitsu is usually formulated outside Japan and may include influences from other martial traditions. The popular Gracie ju-jitsu system, (heavily influenced by modern judo) and Brazilian ju-jitsu in general are excellent examples of Goshin Ju-j-tsu.

Ju-jitsu techniques have been the basis for many military unarmed combat techniques (including British/US/Russian special forces and SO1 police units) for many years.

There are many forms of sport ju-jitsu. One of the most common is mixed style competitions where competitors apply a variety of strikes, throws, and holds to score points. There are also kata competitions were competitors of the same style perform techniques and are judged on their performance. There are also freestyle competitions where competitors will take turns being attacked by another competitor and the defender will be judged on performance.

Description

Japanese ju-jitsu systems typically place more emphasis on throwing, immobilizing and pinning, joint-locking, and strangling techniques (as compared with other martial arts systems such as karate). Atemi-waza (striking techniques) were seen as less important in most older Japanese systems, since samurai body armor protected against many striking techniques. The Chinese quanfa/ch'uan-fa (kenpo or kung fu) systems focus on punching, striking, and kicking more than ju-jitsu.

The Japanese systems of hakuda, kenpo, and shubaku display some degree of Chinese influence in their emphasis on atemi-waza. In comparison, systems that derive more directly from Japanese sources show less preference for such techniques. However, a few ju-jitsu schools likely have some Chinese influence in their development. Ju-jitsu ryu vary widely in their techniques, and many do include significant numbers of striking techniques, if only as set-ups for their grappling techniques.

In ju-jitsu, practitioners train in the use of many potentially fatal moves. However, because students mostly train in a non-competitive environment, risk is minimized. Students are taught break falling skills to allow them to safely practice otherwise dangerous throws.

Technical characteristics common to all schools

Although there is some diversity in the actual look and techniques of the various traditional ju-jitsu systems, there are significant technical similarities:

Students learn traditional ju-jitsu primarily by observation and imitation of the ryu's waza.

The unarmed waza of most schools emphasize joint-locking techniques, that is, threatening a joint's integrity by placing pressure on it in a direction contrary to its normal function, aligning it so that muscular strength cannot be brought to bear, take-down or throwing techniques, or a combination of take-downs and joint-locks.

Sometimes atemi (strikes) are targeted to some vulnerable area of the body; this is an aspect of kuzushi, the art of breaking balance as a set-up for a lock, take-down or throw.

Movements tend to capitalize on an attacker's momentum and openings in order to place a joint in a compromised position or to break their balance as preparation for a take-down or throw.

The defender's own body is positioned so as to take optimal advantage of the attacker's weaknesses while simultaneously presenting few openings or weaknesses of its own.

Weapons training was a primary goal of Samurai training. Koryu (old/classic) schools typically include the use of weapons. Weapons might include the roku shaku bo (six-foot staff), hanbo (three-foot staff), katana (long sword), wakizashi or kodachi(short sword), tanto (knife), or jitte (short one hook truncheon).

Derivatives and schools of jujutsu

Because ju-jitsu contains so many facets, it has become the foundation for a variety of styles and derivations today. As each instructor incorporated new techniques and tactics into what was taught to him originally, he could codify and create his own ryu or school. Some of these schools modified the source material so much that they no longer considered themselves a style of ju-jitsu.

Circa 1600 AD, there were over 2000 ryu (schools) of ju-jitsu in Japan, and there were common features that are characterised of most of them. The technical characteristics varied from school to school. Many of the generalizations noted above do not hold true for some schools of ju-jitsu.

Ju-jitsu was first introduced to Europe in 1899 by Edward William Barton-Wright, who had studied the Tenjin-Shinyo and Shinden-Fudu ryu-ha in Yokohama and Kobe, respectively. Barton-Wright had also trained briefly at the Kodokan in Tokyo. Upon returning to England he folded the basics of all of these styles, as well as boxing, savate and French stick fighting, into an eclectic self defence system called Bartitsu. Some schools went on to diverge into present day Karate, and Aiki styles. The last Japanese divergence occurred in 1905 where a number of ju-jitsu schools joined the Kodokan. The syllabi of those schools was unified under Jigaro Kano to form judo.

Modern judo is the classic example of a 'sport' which was derived from ju-jitsu but is today distinct. Another layer removed, some popular arts had instructors who studied one of these ju-jitsu-derivatives and later made their own derivative succeed in competition. This created an extensive family of martial arts and sports which can trace their lineage to ju-jitsu in some part. Brazilian Jiu Jitsu dominated the first large mixed martial arts competitions, causing the emerging field to adopt many of its practices. The way an opponent is dealt with is also dependent on the philosophy of the teacher with regard to combat. This translates also in different styles or schools of ju-jitsu. Because in ju-jitsu every conceivable technique, including biting, hairpulling, eyegouging etc. is allowed (unlike for instance judo, which does not place emphasis on punching or kicking tactics, or karate, which does not heavily emphasize grappling and throwing) practitioners have an unlimited choice of techniques (assuming they are proficient).

Some old schools of Japanese ju-jitsu

Araki-ryu

Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu

Hontai Yoshin-ryu

Sekiguchi Shinshin-ryu

Sosuishitsu-ryu

Takenouchi-ryu

Tatsumi-ryu

Tenjin Shinyo-ryu

Yagyu Shingan Ryu

Yoshin Ryu

Judo and ju-jitsu

Ju-jitsu was always used in sporting contest, but the practical use in the samurai world ended circa 1890. Techniques like hairpulling and eye poking were and are not considered conventionally acceptable to use in sport, thus they are not included in judo competitions or randori. Judo did, however, preserve the more lethal, dangerous techniques in its kata. The kata were intended to be practiced by students of all grades, but now are mostly practiced formally as complete set-routines for performance, kata competition, and grading, rather than as individual self-defense techniques in class. However, judo retained the full set of choking and strangling techniques for its sporting form, and all manner of elbow locks. Even judo's pinning techniques have pain-generating, spine-and-rib-squeezing and smothering aspects. A submission induced by a legal pin is considered a fully legitimate way to win. It should also be noted that Kano viewed the safe sport-fighting aspect of Judo an important part of learning how to actually control an opponent's body in a real fight. Kano always considered judo to be a form of, and a development of, ju-jitsu.

A judo technique starts with gripping of your opponent followed by off-balancing an opponent, fitting into the space created, and then applying the technique. In contrast, kuzushi (the art of breaking balance) is attained in ju-jitsu by blocking, parrying or deflecting an opponent's attack in order to create the space required to apply a throwing technique. In both systems, kuzushi is essential in order to use as little energy as possible during a fight. Ju-jitsu differs from judo in a number of ways. In some circumstances, jujutsuka generate kuzushi by striking one's opponent along his weak line. Other methods of generating kuzushi include grabbing, twisting, or poking areas of the body known as atemi points or pressure points (areas of the body where nerves venture close to the surface of the skin).

Modern versions of ju-jitsu

A Japanese based martial system formulated in modern times (post Tokugawa) that is only partially influenced by traditional Nihon ju-jitsu, is correctly referred to as goshin (self defense) ju-jitsu. Goshin ju-jitsu is usually formulated outside Japan and may include influences from other martial traditions. The Brazilian Gracie jiu jitsu system, and all Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu in general, although derived originally from judo have evolved independently for many years, and could be considered examples of Goshin Ju-jitsu.

After the transplantation of traditional Japanese ju-jitsu to the West, many of these more traditional styles underwent a process of adaptation at the hands of Western practitioners, molding the arts of ju-jitsu to suit western culture in its myriad varieties. There are today many distinctly westernized styles of ju-jitsu, that stick to their Japanese roots to varying degrees.

There are a number of relatively new martial systems identifying themselves as ju-jitsu.

Post-reformation (founded post 1905) ju-jitsu schools include:

Danzan Ryu

Goshin Ju-jitsu

Hakko Ryu

Hakko Denshin Ryu

Jukido Ju-jitsu

Kumite-ryu Jujutsu

Sanuces Ryu

Shingitai Jujitsu

Shorinji Kan Jiu Jitsu

Small Circle JuJitsu

The following martial arts have derived from or are influenced by ju-jitsu or have founding instructors who studied a derivative of ju-jitsu: aikijutsu, aikido, Bartitsu, Brazilia Jiu-Jitsu, German Ju-Jutsu, hapkido, Hokutoryu jujutsu, judo, kajukenbo, Kapap, karate, kenpo, and sambo.

Etymology

Ju-jitsu, the current standard spelling, is derived using the Hepburn romanization system. Before the first half of the 20th century, however, jiu-jitsu and then jujitsu were preferred, even though the romanization of the second kanji as jitsu is unfaithful to the standard Japanese pronunciation. Since Japanese martial arts first became widely known of in the West in that time period, these earlier spellings are still common in many places. Ju-Jitsu is still the standard spelling in France, Canada and the United States. The martial art is known as Jiu-Jitsu in Germany and Brazil.

Some define ju-jitsu and similar arts rather narrowly as "unarmed" close combat systems used to defeat or control an enemy who is similarly unarmed. Basic methods of attack include hitting or striking, thrusting or punching, kicking, throwing, pinning or immobilizing, strangling, and joint-locking. Great pains were also taken by the bushi (classic warriors) to develop effective methods of defense, including parrying or blocking strikes, thrusts and kicks, receiving throws or joint-locking techniques (i.e., falling safely and knowing how to "blend" to neutralize a technique's effect), releasing oneself from an enemy's grasp, and changing or shifting one's position to evade or neutralize an attack. As ju-jitsu is a collective term, some schools or ryu adopted the principle of ju more than others.

From a broader point of view, based on the curricula of many of the classical Japanese arts themselves, however, these arts may perhaps be more accurately defined as unarmed methods of dealing with an enemy who was armed, together with methods of using minor weapons such as the jutte (truncheon; also called jitte), tanto (knife), or kakushi buki (hidden weapons), such as the ryofundo kusari (weighted chain) or the bankokuchoki (a type of knuckle-duster), to defeat both armed or unarmed opponents.

Furthermore, the term ju-jitsu was also sometimes used to refer to tactics for infighting used with the warrior's major weapons: katana or tachi (sword), yari (spear), naginata (glaive), and jo (short staff), bo (quaterstaff). These close combat methods were an important part of the different martial systems that were developed for use on the battlefield. They can be generally characterized as either Sengoku Jidai (Sengoku Period, 1467- 1603) katchu bujutsu or yoroi kumiuchi (fighting with weapons or grappling while clad in armor), or Edo Jidai (Edo Period, 1603- 1867) suhada bujutsu (fighting while dressed in the normal street clothing of the period, kimono and hakama).

Heritage and philosophy

All Japanese ju-jitsu have cultural indicators which help give a sense of the traditional character of a school. The more traditionally Japanese and the less westernized the school, the more you will see:

An atmosphere of courtesy and respect, a context intended to help cultivate the appropriate spirit.

The type of keikogi or training suit worn, is usually plain white, often with a dark hakama (the most colourful uniform might be plain black or the traditional blue of quilted keikogi; you are not likely to see stars and stripes or camouflage uniforms).

Lack of ostentatious display, with an attempt to achieve or express the sense of rustic simplicity (expressed in such concepts as wabi-sabi in Japanese) common in many of Japan's traditional arts.

The use of the traditional (e.g., Shoden, Chuden, Okuden, and menkyo kaiden levels) ranking system, perhaps as a parallel track to the more contemporary and increasingly common dan-i (kyu/dan) ranking.

The lack of tournament trophies, long-term contracts, tags and emblems, rows of badges or any other superficial distractions.

Japanese culture and religion have become intertwined into the martial arts. Buddhism, Shintoism, Taoism and Confusionist philosophy co-exist in Japan, and people generally mix and match to suit. This reflects the variety of outlook one finds in the different schools.

Ju-jitsu expresses the philosophy of yielding to an opponent's force rather than trying to oppose force with force. To manipulate an opponent's attack using his force and direction, allows jujutsuka to control the balance of their opponent and hence prevent the opponent from resisting the counter attack.

The Japanese have characterised states of mind that a warrior should be able to adopt in combat to facilitate victory. These include: an all-encompassing awareness, zanshin (literally "remaining spirit"), in which the practitioner is ready for anything, at any time; the spontaneity of mushin (literally "no mind") which allows immediate action without conscious thought; and a state of equanimity or imperturbability known as fudoshin (literally "immovable mind").

Techniques

Major categories of ju-jitsu techniques include, but are not limited to:

-

Joint locks can be applied on anything that bends, such as fingers, wrists, elbows, shoulders or knees. Application of locks might include gaining purchase for throwing techniques or restraining an aggressor (such techniques are taught to police forces). Locks can also be utilised for interrogation/torture or controlling a prisoner prior to securing him using rope. In modern sporting contests, bouts are often concluded upon a successful joint dislocation.

-

Including gi-chokes/strangulations (with the lapel), and no-gi. Used primarily to kill or knock unconscious. In combat, a choking technique might permanently dissociate the windpipe from the ligament supporting it, causing death by asphyxiation.

Strangulation techniques may also be used for non-lethal subduing of an opponent. Fully blocking the blood flow to the brain will knock an opponent unconscious in 3 to 7 seconds. To kill by strangulation would take over a minute before brain death occurs.

In modern competition, chokes are normally banned. In the odd case where they are permitted in grappling contests, they are difficult to secure. Strangulation is more popular in competition as they can be applied without fatal consequence, so full leverage can be applied to aid restraining of the competitor. In Ju-jitsu there are many counters to choking or strangling attacks. This has lead to Ju-jitsu's popularity in self-defence applications. There is only one strangle attack which is virtually impossible to counter, unless one is attacked when seated.

-

Strikes are generally taught, though the specific strike preferences vary by system. In Ju-jitsu all known striking techniques are available as tools, nothing is excluded by doctrine. It is the application of those tools that distinguishes different systems of Ju-jitsu. Those students of Ju-jitsu who favour the study of striking went on to help develop Japanese Karate. It is important to realise that Ju-jitsu systems tend not to concentrate on elaborate striking techniques because samurai armour reduces the effectiveness of such techniques in combat. Ju-jitsu emphasises the control of an opponent's balance, and therefore, most systems of Ju-jitsu do not advocate any kicks targeted above the solar plexus. It is reasoned that such kicking techniques compromise one's own balance. Such logic is also central to many striking systems and also advocated by modern-day famous martial arts exponents such as Bruce Lee (despite including many extravagant high kicks in his own movie choreography).

-

Grappling techniques are also common. Simple grappling was incorporated into early Ju-jitsu systems for use in combat. More elaborate grappling techniques and strategies were likely developed for use in sporting contests in the ancient world.

Such techniques have been re-introduced into the Japanese martial arts in post-reformation systems such as Judo and related Brazilian Ju-jitsu systems. In post-reformation Japan, martial arts were altered under the auspices of Jigaro Kano and his contemporaries. They were charged by the government of Japan to 'soften' martial arts training practices to suit a modern world, where training fatalities were deemed unacceptable.

The emphasis on samurai combat skills was degraded in preference to systems maintained, in practice, by sporting competition. Because of this new emphasis, grappling skills have been adapted to modern sporting environments, where gouging, biting, and other unsporting techniques are banned. Only a few schools maintain the old samurai grappling techniques and training practices. The majority of schools utilise Judo training or a more combative form of grappling, evident in schools derived from Japan-Brazilian systems.

-

Throwing techniques discovered by the Chinese/ancient Greek/Indian systems were utilised by the Japanese because they were useful in unarmed combat against samurai in armour. If one were disarmed in the course of combat, such throwing techniques were one's last defence and could be used to floor an armed opponent prior to disarming him. Limited grappling might ensue, but often, victory was secured using smaller weapons such as knives.

-

Biting/gouging/poking/grasping techniques were developed to gain an advantage over an opponent using sneaky methods. Often such techniques were used in counters or defensive situations whilst grappling.

Biting targets include the ears, nose and fingers/hand. Biting can be used against bear hug attacks or in grappling situations on the ground where one can affect release from a grip by maiming the attackers’ fingers, hand or face.

Gouging techniques can be applied to the eyes or genital areas to cause distraction by pain. Gouging can be used in an attacking or defensive situation. Gouging the eyes can be utilised to control the balance of the opponent.

Poking pressure points or the eyes is mostly used as defensive measures prior to counters. Poking is useful in both stand-up defences against grabs of various kinds or against an opponent whilst grappling. It is a vital skill for combat grappling, as often it is the only defence option left if the opponent is dominating the fight. Poking methods include the fingers and knuckles. Often, rings were worn as weapons for use in poking.

Grasping/nipping is useful in defence or attack. Targets include the groin or any parts of the body that contain sensitive areas. Sensitive areas include hair, ears, breasts, nipples, and skin on the inside of the thigh. Applications include distraction as a tool for breaking balance, causing pain for control purposes, escape from pins and locks, and torture.

Atemi is the art of striking pressure points or physiological targets in order to affect kuzushi (the art of breaking balance) or to incapacitate an opponent. As opposed to biting, gouging, poking or grasping, atemi is the art of striking the human body in order to cause specific physiological effects for various applications.

-

Takedowns are distinguished from throws in that a takedown is effected using physical strength or body weight to drag an opponent to the floor or to strike an opponent, thus taking them to the floor. In modern sporting contests, a takedown may result after a successful clinch in which the opponent’s legs and/or arms are trapped, preventing him from retreating. To floor the opponent without the use of kuzushi (the art of breaking balance) means brute force over skill or technique. One may break the balance, but not by skilful manipulation of the opponent's motion, but rather by the forced constriction of movement followed by physically overcoming the opponent. Takedowns often result from an accident during a sporting contest or because of an over-aggressive attack.

The important distinction is that a throw is affected by minimum physical strength and maximum use of kuzushi. A takedown often uses a lot of physical strength, and there is no art to the method of breaking balance.

Differences in Technique Application

There are differences in application of the same technique between styles of ju-jitsu that range from the minor to the major.

-

When performing a forward shoulder roll, some styles roll on the back of the lead hand (i.e. palm up), and some roll palm down.

-

Some styles perform wrist locks (or "peels") with the bottom 3 fingers and don't use the index finger, and some use the top 3 fingers to keep the pinky off. The intent of both approaches is the same: do not block the opponent's wrist during a peel.

-

Some styles advocate using a "live hand" (hand open) for an armbar takedown, whereas some advocate making a fist. Adherents of each approach claim "more power", though the closed-fist approach arguably offers the additional benefit of reducing the possibility of a finger getting accidentally snagged.

-

On a hip throw off the right hip (for example), the most common way this throw is taught is to grab the uke's right arm with the left hand. Some styles, however, teach "wrapping" the uke's right arm with the left instead of the grab. Biomechanically, the most effective method is to grab the right upper arm using a monkey-style grip.

Using this method, one grips the opponent's left arm using the 4 fingers and the thumb against the palm (instead of gripping with the thumb against the 4 fingers). The reason for using this grip rather than a normal human gripping action is that the thumb gripping against the 4 fingers is weaker in strength than the grip applied by the 4 fingers and thumb against the palm (as monkeys do when gripping the branch of a tree to swing). Grabbing the upper arm rather than the wrist allows the body greater pulling torque.

Likewise, on hip throws, some systems grab around the waist (or, in ignorance, the belt), and some systems prefer to wrap tori’s right arm under the uke's left. One should never grip the opponent’s belt; modern attire may not include a belt. In fact, grabbing the belt is not necessary. Simply grabbing around the waist (so long as the grip is all the way around the waist) works better, anyway. One should note that it feels easier to grab your opponent’s waist with your right arm than it does to wrap your right arm around your left arm. Biomechanically, grabbing the opponent higher up the back (such as at the shoulder) can allow the opponent to bend at the waist, making the hip throw more difficult. The sequence of actions required for the hip throw is: block, parry, or deflect the opponent's punch if necessary, effect kuzushi (the art of breaking balance), bend the knees and turn whilst pulling the opponent over your hip.

-

The biggest conceptual difference is when grappling is taught, whether a style views grappling as a sport or grappling as a necessity of balanced self-defence training (or both). Both applications have merit, and the training will have a considerable amount of overlap but will also have important differences. The latter approach will need to understand the fundamentals of the grappling positional hierarchy like the former, but the priority will be to get off the ground (and get away) as fast as possible. It is also a very good technique to use when near an opponent.

-

The two primary schools of thought in ju-jitsu and ju-jitsu-derivative systems for weapons defence are whether "the best offence is a good defence" or "the best defence is a good offence." An example of such philosophy: is it best to imagine that an opponent's knife makes no difference to his attack and to simply defend as usual? Perhaps it is better to adapt the technique defensively to avoid the possibility of being slashed or stabbed.

Obviously, in the modern world, weapons defence is less effective because of the use of firearms. The only feasible defence against a gun is when the aggressor points a gun into your back prior to demanding your wallet, for instance. In this situation, putting one's hands up and turning on the spot can push the gun out of your path before the aggressor can pull the trigger.

As in all aggressive situations, a defensive approach is considered safer than an offensive approach. If you are threatened with a weapon, escaping or defusing the situation is preferable to an aggressive response, which may lead to injury or death.

Weapons

Katana is a type of Japanese backsword or longsword, the term is also frequently misused as a general name for Japanese swords. In use after the 1400s, the Katana is a curved, single-edged sword traditionally used by the samurai. Pronounced [kah-tah-nah] in the kun'yomi (Japanese reading) of the kanji, the word has been adopted as a loan word by the English language; as Japanese does not have separate plural and singular forms, both "katanas" and "katana" are considered acceptable plural forms in English. The katana was typically paired with the wakizashi or shōtō, a similarly made but shorter sword, both worn by the members of the warrior class. It could also be worn with the tantō, an even smaller, similarly shaped blade. The two weapons together were called the daishō, and represented the social power and personal honor of the samurai. The long blade was used for open combat, while the shorter blade was considered a side arm, more suited for stabbing, close-quarters combat, decapitating beaten opponents when taking heads on the battlefield, and seppuku, a form of ritual suicide.

Japanese swords are fairly common today; antique and even modern forged swords can still be found and purchased. Modern nihontō are only made by a couple of hundred smiths in Japan today at contests hosted by the All Japan Swordsmiths Association.

The Naginata

Naginata is a pole weapon that was traditionally used in Japan by members of the samurai class. It has become associated with women and in modern Japan it is studied by women more than men; whereas in Europe and Australia naginata is practiced predominantly (but not exclusively) by men. A naginata consists of a wood shaft with a curved blade on the end; it is similar to the European glaive. Usually it also had a sword-like guard (tsuba) between the blade and shaft.

The martial art of wielding the naginata is called naginata-jutsu. Most naginata practice today is in a modernised form, a gendai budo called Atarashii naginata, in which competitions also are held. Use of the naginata is also taught within the Bujinkan and in some koryu schools. Naginata practitioners may wear a modified form of the protective armour worn by kendo practitioners, known as bogu.

The Bo

A bō or kon, is a long staff, usually made of tapered hardwood or bamboo, but sometimes it is made of metal or plated with metal for extra strength; also, a full-size bō is sometimes called a rokushakubō. This name derives from the Japanese words roku, meaning "six"; shaku; a Japanese measurement equivalent to 30.3 centimetres, or just under 1 foot; and bō. Thus, rokushakubō refers to a staff of about 6 shaku (181.8 cm, about 6 ft.) long. Other types of bō range from heavy to light, from rigid to highly flexible, and from simply a piece of wood picked up off the side of the road to ornately decorated works of art.

The Japanese martial art of wielding the bō is bōjutsu. The basic purpose of the bō is to increase the force delivered in a strike through leverage, and to benefit the wielder from the extra distance this weapon affords. The user's relatively slight motion, effected at the point of handling the bō, results in a faster, more forceful motion by the tip of the bō against the object or subject of the blow; thus enabling long-range crushing and sweeping strikes. The bō may also be thrust at an opponent, allowing one to hit from a distance. It also is used for joint-locks, thrustings of the bō that immobilize a target joint, which are used to non-fatally subdue an opponent. The bō is a weapon mainly used for self-defense, and can be used to execute several blocks and parries. Martial arts techniques, such as kicks and blocks, can also be combined with weapon techniques when practicing this martial art to enhance its effectiveness.

Although the bō is now used as a weapon, its use is believed by some to have evolved from non-combative uses. The bō staff is thought to have been used to balance buckets or baskets. Typically, one would carry baskets of harvested crops or buckets of water or milk or fish, one at each end of the bō, that is balanced across the middle of the back at the shoulder blades. In poorer agrarian economies, the bō remains a traditional farm work implement. In styles such as Yamani-ryū or Kenshin-ryū, many of the strikes are the same as those used for yari (spear) or naginata (glaive). There are stick fighting techniques native to just about every country on every continent.

A set of Sai

The sai (釵) is a weapon found predominantly in Okinawa (there is evidence of similar weapons in India, China, Malaysia and Indonesia). Sai are often believed to have originated as an agricultural tool used to measure stalks, plow fields, plant rice, or to hold cart wheels in place, though the evidence for this is limited. Another belief, perhaps not as widely held, is that they were modeled after the San-Ku-Chu. Its basic form is that of an unsharpened dagger, with two long, unsharpened projections (tsuba) attached to the handle. The very end of the handle is called the knuckle. Sai are constructed in a variety of forms. Some are smooth, while others have an octagonal middle prong. The tsuba are traditionally symmetrical, however, the Manji design developed by Taira Shinken employs oppositely facing tsuba.

The sai's utility as a weapon is reflected in its distinctive shape. With skill, it can be used effectively against a long sword by trapping the sword's blade in the sai's tsuba. There are several different ways of wielding the sai in the hands, which give it the versatility to be used both lethally and non-lethally.

Traditionally, sai were carried in threes, two at the side, as primary weapons, and a third tucked behind, in case one was disarmed or to pin an enemy's foot to the sandy Okinawan ground. As a thrown weapon, the sai have a lethal range of about 20-30 feet. Throwing the sai was typically used against an opponent with a sword, bo or other long range weapon. The heavy iron (or in contemporary versions, steel) sai concentrate enough force to punch through armor.

One way to hold it is by gripping the handle with all of your fingers and hooking your thumbs into the area between the tsuba and the main shaft. This allows you to change effortlessly between the long projection and the back, blunt side. The change is made by putting pressure on your thumbs and rotating the sai around until it is facing backwards and your index finger is aligned with the handle. The sai is generally easier to handle in this position. The knuckle end is good for concentrating the force of a punch and the long shaft can be wielded to thrust at enemies, to serve as a protection for a blow to the forearm or to stab as one would use a common dagger.

Some keep the index finger extended in alignment with the center shaft regardless of whether the knuckle end or the middle prong is exposed. The finger may be straight or slightly curled. They keep the other fingers on the main shaft and the thumb supports the tsuba.

The above grips leverage the versatility of this implement as both an offensive and defensive weapon. Both grips facilitate flipping between the point and the knuckle being exposed while the sai is held in strong grip positions.

In Hollywood, however, sai are portrayed as a much more offensive weapon. They are used like a combination of a sword, dagger and a throwing dart often on the big screen. Little play is given to striking with the knuckle. Thus, the normally unsharpened weapon is portrayed as a sharpened one. E.g., Jennifer Garner who played Elektra Natchios in Daredevil and its spin-off Elektra uses the sai as an offensive weapon. She can be seen holding her sai in a very offensive way (with the index and middle finger straddling the middle prong inside the tsubas). A grip with 2 or 3 fingers inside between the tsuba and the middle shaft facilitates a slightly more flashy array of finger twirls. However, it eliminates certain defensive possibilities and knuckle strikes.

In truth, a practitioner moves his fingers and alters his grip reflexively to execute different techniques as needed. It is unlikely that one would truly use a particular grip uniformly.

The jitte is the one-pronged Japanese equivalent to the (Okinawan) sai, and was used predominantly by the Japanese police during the Edo period. It is a featured weapon in the curriculum of several Japanese Ju-jitsu and koryu schools.

An interesting footnote is that the Sai looks strikingly similar to the Greek letter Psi (pronounced identically in English).

Tonfa

Tonfa; Folklore says these were originally used as wooden handles that fit into the side of millstones and were later developed into weapons when Okinawan peasants were banned from using more traditional weaponry. Other sources say they have a richer history, extending back into Chinese martial arts, and appearing in Indonesian and Filipino cultures. It also appears in Thailand as the Mae Sun Sawk. The difference is that the Mae Sun Sawk has rope tying the elbow end of it to the arm. The tonfa traditionally consists of two parts, a handle with a knob, and perpendicular to the handle, a shaft or board that lies along the hand and forearm. The shaft is usually 51–61 cm (20–24 in) long; optimally, it extends about 3 cm past the elbow when held. Often the shaft has rounded off ends which may be grooved for a better grip. There is a smaller cylindrical grip secured at a 90 degrees angle to the shaft, about 15 centimetres from one end. There are numerous ways to defend and attack with the tonfa. Defensively, when holding the handle, the shaft protects the forearm and hand from blows, and the knob can protect from blows to the thumb. By holding both ends of the shaft, it can ward off blows. When holding the shaft, the handle can function as a hook to catch blows or weapons.

In attack, the shaft can be swung out to strike the target. By holding the handle and twirling the tonfa it can gain large amounts of momentum before striking. The knob can be used as a striking surface, either when held by the handle, or when holding the shaft, using it as a club (when striking with the flat end) or like a hammer (when striking with the handle itself, which is an effective application of force amplification). The shaft can also be maneuvered to stab at attackers. By holding the shaft and handle together, the tonfa can be used for holding or breaking techniques. Another method as used by the Thais involves striking with the elbow end of the mae sun sawk while grabbing the handle similar to striking with the elbow in Muay Thai or Krabi Krabong. As the mae sun sawk has the elbow part of the arm attached to it, the swinging out technique described above cannot be used but offsetting that, almost all of the elbow strikes of Muay Thai can be used with great power.

Tonfa are traditionally wielded in pairs, one in each hand, unlike the police nightstick which is a single-hand weapon. As the tonfa can be held in many different ways, education in the use of the tonfa often involves learning how to switch between different grips at high speed. Such techniques require great manual dexterity, as they involve flips and slides with the weapon.

The nunchaku (Chinese: shuāng jié gùn; liǎng jié gùn "Dual Section Staff"; èr jié gùn "Two Section Staff"; Japanese: nunchaku shōshikon "Boatman's staff"; sōsetsukon "Paired sections staff"; nisetsukon "Two section staff", also sometimes called "nunchucks", "numchuks", or "chain sticks" in English) is a martial arts weapon of the Kobudo weapons set and consists of two sticks connected at their ends with a short chain or rope. The other Kobudo weapons are the sai, tonfa, bo, eku, tekko, tinbe-rochin, surujin, and kama. A sansetsukon is a similar weapon with three sticks attached on chains instead of two.

Although the certain origin of nunchaku is unknown (as with most weapons in history), it is thought to come from either China or Okinawa; and according to the History Channel they were created in their current incarnation for the movies. The Japanese word nunchaku itself comes from the Min Nan word ng-chiat-kun. When viewed etymologically from its Okinawan roots, nun comes from the word for twin, and chaku from shaku, a unit of measurement. The popular belief is that the nunchaku was originally a short flail used to thresh rice or soybeans (that is, separate the grain from the husk). An alternative theory is that it was created by a martial artist whose staff was broken in three pieces in combat and then strung together, creating what is commonly known today as a three section staff, and that nunchaku were derived from that weapon. It is also possible that the weapon was developed in response to the moratorium on edged weaponry under the Satsuma daimyo after invading Okinawa in the 17th century, and that the weapon was most likely conceived and used exclusively for that end, as the configuration of actual flails and bits are unwieldy for use as a weapon. Also, peasant farmers were forbidden conventional weaponry such as arrows or blades so they improvised using only what they had available, farm tools such as the sickle. Regardless of the origin of the nunchaku, the modern weapon would be an ineffective flail.

The nunchaku as a weapon has surged in popularity since martial artist Bruce Lee used it in his movies in the 1970s. It is generally considered by martial artists to be a limited weapon. Complex and difficult to wield, the nunchaku lacks the range of the bo (quarterstaff) and the edged advantage of a sword. It is also prone to inflicting injury on its user. Nonetheless, the nunchaku's impressive motion in use and perceived lethality contributed to its increasing popularity, peaking in the 1980s, perhaps due to its unfounded association with ninja during the 1980s ninja craze.

Kama are Okinawan and Japanese weapons that resemble traditional farming devices similar to a scythe. It was originally a farming implement used for reaping crops. During the annexation of Okinawa by the Satsuma, all traditional weapons were outlawed. This led to the development of the kama and other Kobudo weapons. It is sometimes known as a 'Hand Scythe'.

When a ball and chain are attached to the end of the Kama, it becomes a kusarigama, a formidable (if hard to master) weapon because its range makes it extremely difficult for opponents to approach the wielder.

A similar weapon called Lian, possibly an ancestor of the Kama, existed in China since ancient times.